It’s disconcerting to read the headlines. State’s Pre-K Program Wins Praise, but Lost Funding and Slots Last Year, Per-student Pre-K Spending Lowest in Decade, Report: Nevada Slipping in Pre-K Program Funding,….. We could go on, but the point has been made. Much of the news stems from the National Institute for Early Education Research’s The State of Preschool 2012 which highlights among other things that nationwide funding for Preschool dropped by $500 million over the past year with enrollments unchanged at 28% (Barnett, Carolan, Fitzgerald, & Squires, 2012). That’s disturbing, particularly against the backdrop of Sean Reardon’s NY Times blog, No Rich Child Left Behind, which paints a worrisome picture of the growing academic gap between children from rich families versus those of poor families.

We know the brain is plastic and malleable, responding to the environment through the growth and expansion of neural networks. And we know the plasticity is especially vigorous during the early years of life. We also know how critical the first few years of life are to vocabulary acquisition and literacy. Hart and Risleys’ Meaningful Differences was a game changer and a must-read for any educator or policy maker. My first read of the seminal study led me to call both researchers pleading for answers on how to make a difference I and my like-minded colleagues so desperately sought when it seemed much of a child’s script for future success was being written before he or she ever entered a school setting. Both researchers gently walked me off the ledge by assuring me we can and must make a difference, particularly through increasing family connections with schools.

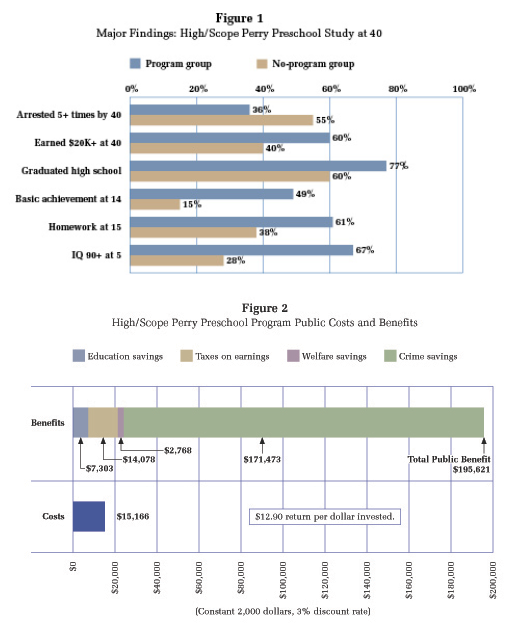

Pay a little now, or a lot later. From the 2005 HighScope Perry Preschool Lifetime Effects Through Age 40 study, the costs of not having preschool are alarming (See figures below). Compared with the program group, those students that did not participate in a preschool program were more apt to be arrested, more likely to earn less money at age 40, less likely to do their homework at age 15, more likely to have a higher IQ score at age 5, and so on. Preschool program graduates ultimately save society nearly $200,000 per child through reduced public service costs. There are many, many more studies that demonstrate the cost savings and social-emotional benefits of quality preschool programs on children and society.

Experiential deficits the majority of poor students bring to school are extensive, particularly when we wait till they reach kindergarten age to start them in school. Unfortunately, the costs of waiting till kindergarten to remedy the deficits are far greater than those of universal pre-k funding. From Albert Wat (2007), author of Dollars and Sense: A Review of Economic Analyses of Pre-K, “Ultimately, behind the numbers about costs and benefits….., the studies…illustrate what educators and parents have known for years, that children who participate in pre-k do better academically, physically, and socially throughout their lives….In the end, we all live in a safer, more productive, and more educated society.”

It makes no sense to not invest in our future. We know the savings preschool programs offer, and we know the costs when such programs are unavailable. The math is quite simple. Spend a little now to remedy the gaps between the privileged and unprivileged students, or spend a lot more years from now trying to fix the consequences. All children deserve no less than to enter our schools on a level playing field, and to be equally prepared for college and career after graduating high school. Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

Barnett, W.S., Carolan, M.E., Fitzgerald, J., & Squires, J.H. (2012). The state of preschool 2012: State preschool yearbook. New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research.